Howard Pastiche – Conan of Aquilonia (L Sprague de Camp, 1977)

There is a sense of contrary in Howard. On the one hand, the iron-thewed champion bares his chest to the elements; on the other, delicate fronds and buds blossom forth in poetic prose. The quiet repose of nature’s bounty, the feminine side that the hero voyages amongst. He is not disconnected from nature’s harvest like the false Apollo; he accepts life’s rich harvest, and with it the regenerative forces of spring, the sombre glory of autumn. Death is his companion and he does not shy from it.You can call this the mythos of grimness and the dark force that injects itself into Howard’s prose that is said to be lacking in de Camp. I suppose there’s a lot in that but, equally, there is a gentleness. This extract from “By This Axe I Rule”, for example

A cool wind whispered through the green woodlands. A silver thread of a brook wound among great tree boles, where hung large vines and gayly festooned creepers.. She was not aware of his presence until he knelt and lifted her, wiping her eyes with hands as gentle as a woman’s.

The little slave girl looked into a dark immobile face, with cold narrow grey eyes which were just now strangely soft.

Howard establishes wide-ranging deities associated with Conan’s loves and losses. Ishtar, Mitra, the triumph of love over death in “Queen of the Black Coast”. In Belit’s origin story, Roy Thomas has her mistaken for Derketa, goddess of love and death, by her black tribesmen. Regeneration, the everlasting scene of dawn awakening over her funeral pyre. These are the blood-tinged images of an epic song-cycle.

Thomas is quite indebted to de Camp’s expansion of the mythos where Conan and Thoth Amon have their ultimate encounter. As the Aquilonians march southward, they encounter what you might call Howardian perils. In Conan’s battle with Set/Damballah (“Moon of Blood”), it becomes clear that Shemitish sorcerer Nemaunir has materialized a serpent of the moon itself.

Into the shadowy battle of wills he threw his courage, his manhood, and his very lust for life.. The cold intelligence of that transmundane being knew that it could in time destroy the earth and quench the fires of the very sun. (p 123)

This might lead you to say that in this philosophy the moon is a source for blood-spawned savagery, and the sun a shining beacon of enlightenment? But no, this is a sorcerous moon presaged by a lurid eclipse.

A red shadow with a curved leading edge had begun to creep across the face of the moon. (p 120)

This is no more the true moon than the false Apollo is the true Apollo. Sorcery is a twisting and mangling of the balance of cosmic forces to achieve a tyranny on Earth. You notice that the worship of Mitra, or Crom, is kept at arm’s length and the gods of the sky are not approached too closely. Only sorcerers require the closeness to put them on a par with deities and bend them to their unholy wills. The sorcerer is the tyrant that does not recognize a contrary in nature.

The content of Howard is composed of contraries. You can have a pastiche that doesn’t articulate the delicacy of nature as de Camp does here..

Now they stood knee deep in the lush grass of a velvety meadow, spangled with small flowers, white and blue and scarlet. In the middle distance a herd of long-horned cattle placidly cropped the herbage. (p 136)

..but, in that case you will only have stylistic blood-and-gore without the underlying philosophy, gung-ho style without Howard’s content. The basic point is grimness is not a death-wish. It’s not just blood-letting. It’s a berserker gaiety in the face of death. De Camp may not catch this, but it’s worse by far to abandon the philosophy and have no regenerative spirit.

Pastiches abound which have no trace of Howard’s gentle side, and this gives rise to mistaken notion. See Parache, para "Reflections about the Death of Robert E. Howard" http://www.robert-e-howard.org/howardiana1.html

For those writers like Robert Jordan where anything goes so long as it’s blood-bedraggled scenes of grim roistering, this is only half of Howard’s content. The other is the quiet solitude of nature, a Dionysian vastness through which the hero voyages. Brute force and quiet grace both have a place in a neverending adventure, blood-red dawn of an epic song-cycle.

Belite in Comics

Belite is such a fantastically romantic creation it’s interesting to see how the decidedly classical Buscema dealt with the stories woven by Roy Thomas around the original “Queen of the Black Coast”. BWS’s style is what he calls “New Romantic”, but of course it’s also classic and anatomical. What he means by New Romantic is probably the sense of mystical in nature, the way in which the meanings of the picture are like a jigsaw puzzle – like “The Ram and the Peacock”.

The meaning of that picture is quite Howardesque, with the contrary motifs of savage barbarian, the fallen wizard, wind-chimes in a garden sanctuary. BWS’s images are inimitable, but there is something to be said for the bold-brushed approach brought by Buscema/Chan to the Roy Thomas Belit issues.

Chan’s loose, ultra-bold brush-strokes add a romantic thrust to Buscema’s more stolid footwork. Indeed, Thomas says in Chronicles #11 that the Howard Chaykin issues are just as much Chan’s. His lines have a powerful grace that evokes classic comic strip art.

Since the entire cycle of stories from Belit’s appearance in #58 to her death in #100 is pure romance – in content – one can approach the imagery from that standpoint. Thomas never strays too far from the Howard mythos, unlike some writers, so what you are looking at has a good mix of content and style.

There's a quote from a letters page in Red Sonja #4 in defence of Frank Thorne that goes

What you look for in a budding artist is not how "well" they draw, but how well they move the story on. Panel to panel continuity, it all flows together.

This is quite a useful definition of style because it depends so much on penmanmship. We all know about BWS's hatching technique that owes more to 18th century British caricaturists than US strips. Thorne is another one whose technique is holistic, and he even does the lettering. Buscema may be one of the better draftsmen, but one cannot overestimate the effectiveness of a very defined brushstroke that adds stylistic flourish to the form. What you see is Chan's woodcuttish density, and it makes the whole thing more holistic.

As the quote says, it's not realism because you are reading a narrative, a design, a curvilinear flow (another reference is CC Beck in TCJ ). I'm only emphasizing this because the Belit stories can be seen as a cycle of love, adventure, death (rebirth). Thomas brings along a lot of extraneous mythos as it goes, but the overall consistency of style provides a counterbalance of simplicity.

This is going back a bit (to the 50s) but in TCJ #121 CC Beck likens the craft of comics to other things like batik, cross-stitch embroidery, where the actual aim of the design is simplicity (Crusty Curmudgeon, “Are Comics Art or Craftwork?”).

This is true of other comics.* Walt Simonson's Thor expanded on the mythos greatly but his cleancut style made it very approachable. This mix of expanded mythos with strong, decisive style (not realism) is what makes comic work. Contemporary comics have sold out to the mistaken notion of realism and become mostly unreadable, but that's by the way!

This isn't about realism. It's about the romance of the story, the mix between classical and romantic in the style. Chan's hefty inking brushes against romance and adds a frisson that runs through the stories. Basically, the romance Chan adds tends towards an expressive, Dionysian quality, away from realism. The style therefore fits the content of a story-cycle which is tragic.

I hope that makes the point that romance – or romantic-classical – is nigh indispensable for the reading of content. It's about the balance between reason and expression because any story contains both. Because classic comics are so good at this, you could look at them as a rebellion against a world of reason and order. The false Apollo or the talking head.

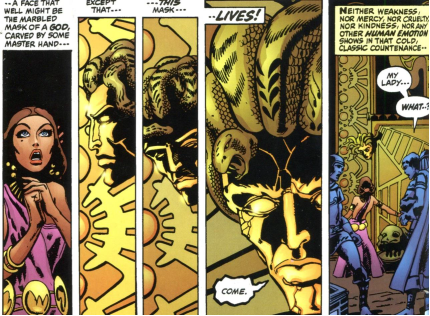

Conan #7, BWS art, “The God in the Bowl”, an emissary of Thoth Amon (© Marvel 1971)

The balance between reason and expression. Artists, like most creators, get ideas from their unconscious. What I really like about Thomas’s Belit is that he makes ample use of the earlier images in the series. Thoth Amon makes a fleeting appearance in Conan #7, and BWS’s sweeping ram’s head horns make a reappearance in #89. This image, which seems to extend the head beyond its normal reach, seems to tap into levels of our unconscious fears.

Conan #89 (© Marvel 1978)

Fear of megalomania; of egocentricity allied to a world-devouring cunning. The authoritarian sweep of that horned head says it all.

Thomas also makes ample use of de Camp’s pioneering work in amalgamating the mythos from Kull and Conan. As he says, under de Camp’s pen Thoth became the villain supreme and I, for one, am willing to overlook supposed stylistic flaws! Under Thoth’s control are two races of The “serpent-man” from Kull, and the “man-serpent” from the story “The God in the Bowl”.

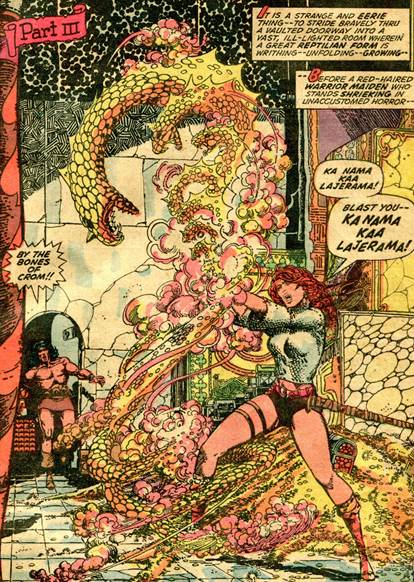

Thomas makes another BWS reference here to the serpent tiara from Conan #24. As you may recall, Conan had no clue that Red Sonja was contracted by the King of Pah-Dishah to steal the tiara when they broke into the tower of Makkalet. She utters the words..

too late to prevent the tiara mutating form. (© Marvel 1972)

As the supremo of The Black Ring, Thoth’s aim is to bend the world to his yoke of a single dominant ego, a calculating brain of inhuman power vested in control of snake-men who follow his every whim.

Our three adventurers Conan, Belit and Zula survive to match their wits and freedom of thought and action – mind and body – against the world-encircling egocentric ram’s head of Thoth Amon.

Now, if comics are a form of rebellion against a world of reason and order, how is it apparent in the Howardian mythos outlined? For a start, expression can have a Dionysian simplicity of design, like the ram’s head horns. It comes from the unconscious, so you already have a type of rebellion against a world of reason. The simplicity of design, like BWS’s heraldic prints, speaks for itself.

In our world we have talking-heads. That is, heads without bodies, so you could image they’re either snake-heads, selling lies, or human heads with snake bodies. The false Apollo. That would mean our world was essentially fake, because a head is not a whole person. Mind and body. The hero, and of course the superman, are the ideal of mind allied to super-fit body.

Assuming our world is fake – like Topeka – you might assume there was something fantastical about it. Something from the unconscious. If the human heads are subservient to something, it could be something like the world-encircling, calculating, sweeping horned head of Thoth Amon.

Thoth Amon is not real, he’s fantasy, he springs from the unconscious. But the unconscious is part of reality. In our world of reason, the megalomaniac, calculating figure of Thoth is fantasy, but he still exists in our subconscious. You can’t see him, but his egocentricity still ascends to world domination.

That is the scary part of the subconscious; we don’t know what’s there. Artists and fantasy creators access the unconscious strands of thought and desire. If we live in a world of fake heads, the truth may be in the fantasy that we can’t see, the subconscious desires.

In the 60s there were rebels, but how do you rebel against something invisible and omnipotent?

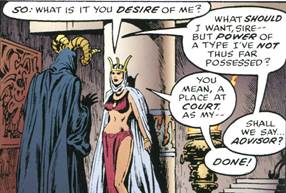

© Marvel 1978

Home