Dr Strange and Ant-Man

Once outside of “the dominion of fact” – a phrase applied to REH’s historical tales – you’re back in a more traditional depiction of a culture, which is something of style and something of content. A good example is Doctor Strange’s Greenwhich Village milieu and Sanctum Sanctorum. All the hints of magical forces and hidden doors are closely tied-up with the delirious décor as depicted by Ditko.

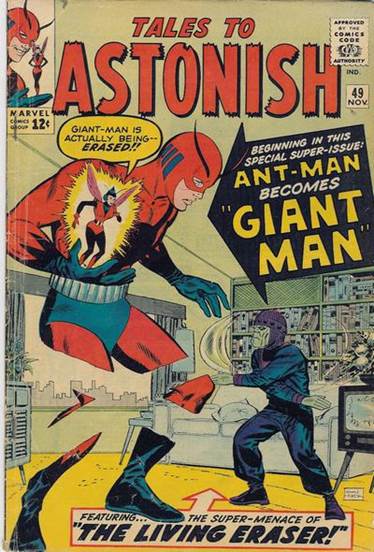

© Marvel 1964

The two are pretty inseparable, and you could easily call it a magical ecosystem. Doctor Strange has his fortress, his Eye of Agamotto, his mementoes, the Temple of Man, the link to the Ancient One, the aid of his otherworld disciple and sometime love Clea. Strange is at his strongest on his own turf. Artists are tied-up in the style, so the survival of the ecosystem is a large part of the story.

What this means is even if there is a linear story, a lot of it isn’t linear since it’s tied-up in depicting the culture of survival, the décor, the mystic tokens. A lot of this comes from the unconscious, from the artist’s imagination. Otherworldly images of Phantoms speak of the struggle with death; Clea speaks of rebellion and love. The irrational aspects of life take on a much greater dimension, but this is true of all traditional cultures which must live within the cycles of creativity and destruction.

So in the 60s comic, Dr Strange’s role of Master of the Mystic Arts was as Earth’s curator of an irrational universe harbouring all manner of destructive forces. Dormammu, dread overlord of the Dark Dimension holding captive the rebel Clea; Umar, his vengeful sister, who is freed when Strange overthrows Dormammu..

Strange may win battles, but he is in his irrational universe where the dark forces of destruction, death, chaos and Nightmare must always exist. He is there to protect mortals from their spillover; he is in a Manichean place and cannot break through to the rational world of humdrum normality.

Strange’s magical ecosystem has this balance that I think he would recognize; he cannot destroy these dark forces, only keep them at bay. To destroy them he would have to live in the humdrum world he has forsaken. All of this the film seems to miss since it completely avoids his milieu and the whole culture of magical gamekeeping. It seems in the film there are forces that must be repelled from the rational world, but the actual point of an irrational ecosystem is never really broached.

So, what is the point of an irrational ecosystem? Basically, survival, since we all confront death, destruction, chaos and nightmare. It’s not a linear system of “fact”, it’s an existential one of rebellion since you are breaking free of the dominion of fact. Linear facts cannot tolerate a cyclical system but, actually, all traditional cultures are cyclical, encompassing a wider cycle of creation and destruction.

CROWN OF CREATION

Irrational forces take the place of policy, acting like a religio-culture. If you’re an Indian Hindu you must respect cows and the local deity because that’s the culture, not for any other reason. This is pretty much like an eco-culture, something that brings humans into the presence of other lifeforms. An eco-culture has a drama of its own; taking products to market on a donkey for example. As the rhyme goes, if you’re taking a piggy to market it may well be to kill it. It’s a bloody act of death and survival. At once you’re connected with natural cycles. The dilapidated districts of New York’s meat-packing yards and wharfs have inspired a number of comic book milieu, from The Spirit to Daredevil .

There is drama there that modern gentrified NY has lost. Now, you might say the Hudson has been taken over by events, which you have to sort of saddeningly shrug your way through in resigned modern fashion? You might, but if you widen it to the whole of America there is an ideal at stake, the idea of a place that has no hand of government in it, that just happens. It’s an idea that goes through American history and the Wild West, and there is a dark side to it. The history of outlaws and blood-letting and gang-law, Hell’s Kitchen.

It’s also what one thinks of as the iconic side, The High Chaparral and the sturdy sense of solidarity, Texas steers in the red dust of the cowboy trail. What I’m basically getting at is the American ideal is tied-up with the idea of creation and destruction, prairies and lakes “from sea to shining sea”. It’s an eco-culture before it’s a political one. It’s interesting that president Trump, a non-politician, points to the “fake” press while himself seeming to have no sense of the iconic eco-culture – from west to mid-west to east-coast. He is all policy.

Comics do have this sense, so here ends the digression! A lot of Marvel Studios’ adaptations I se as gentrified versions of the iconic original. Dr Strange’s demonic entities are a darkness that also exists in the heart of nature. Ant-Man, meanwhile, could be something like a cowboy icon who takes to ants.

Scientist/adventurer Hank Pym shrinks along with his lab love, the athletic brunette Janet Van Dyne. As Ant-Man and the Wasp, they manage to learn to communicate with ants using cyber-helmets of a patented design and train them as valiant mounts. This mix of brain, brawn and beauty in a techno-organic setting is pure pulp, with a self-contained ecosystem. The film saw fit to ditch all that interesting culture for a straightforward adventure yawn.

The emphasis on style in comics seems to lend itself to well-developed milieux, the weirder the better. In “Journey to the Centre of the Vision” Pym enters the chest-cavity of the android Avenger. He’s careful to ensure the safety of his faithful steeds.

Neal Adams art, Avengers #93, © Marvel 1971

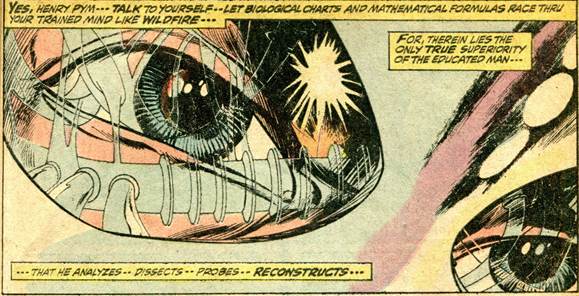

Style is not content; it’s something dynamic that animates a milieu. Comics seem to employ the relationship between the two to great effect. Pym is introspective; he represents a type, a man of action and thought, a doer. Comic artists represent a similar type. They perfect their craft and tell stories brought to life partly from their unconscious desires, images.

This is the same type as the early 30s art-literary club of like-minded prairie-poets that REH joined – the Junto. Viewed as an institution, it was an enclave of pulp rebels against oil and industry. Pulp writing attracts a certain type, the thinker who appreciates action, the mixture of introspection and savagery.

This invites a kind of meta-culture born of unconscious imagery, desires, urges. Meta meaning beyond human, connecting them to the wild side. It might be said “the wild” has a dark side and a gentle side.

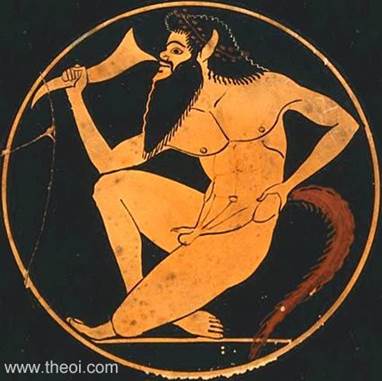

Satyr holding drinking gourd, Athenian red figure, 5th century

The dark side has a sense of unreality that is associated with pulp fantasy.

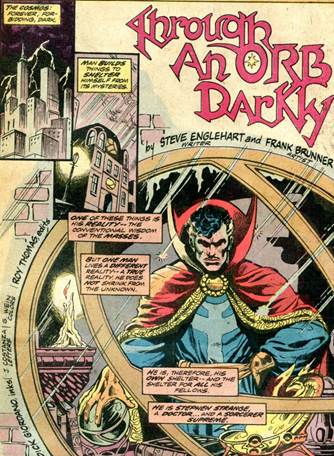

Doctor Strange #1, © Marvel 1974

Englehart paints Doctor Strange as a custodian of the irrational, the deathly. The final panel of #5, meanwhile, has the Alice in Wonderland type unreality become a trap for the egotistical Silver Dagger.

Doctor Strange #5, © Marvel 1974

Strange, as Englehart says, deals in forms that are irrational, even approaching unreality. However, that’s not the same as fake, meaning untrue. If they exist in the unconscious they are real enough, they just have the appearance of unreality. This points to something that the 30s Junto seem to personify. The mixture of introspection and action is a meta-culture because it goes beyond the human-centric, the egoistic to images of the unconscious.

A meta-culture represents a certain type – the artist – a type of reaction against the complexity of the ego and toward iconic imagery of the imagination. What you can say is that a meta-culture is very common in history and points to dark irrational forces, as well as gentle images of nature.

This takes us to Howard’s historical tales “free of the dominion of fact” - see Swordwoman and other Historical Adventures, Del Rey - set in medieval Europe and points East. The great conflagrations of Vienna and Ottoman, of Jerusalem knight and Saracen against eastern hordes, are like a fiery, dreamlike fury. What gives these blood-drenched epics their docudrama realism?

I would say it’s the presence on the stage of the unreal, of great shadows of men and beasts, what today is sometimes called magic realism. How is it that the unreal can seem more real? Because it’s an introspective reality seen through the desires of men and women.

Let me take you back to the 13th century, of government by city-states, of news by horseback. Writing of that time, there is very little “fact” as we know it. There is a mix of introspective content and actual events, which are what Howard is writing about. His writing is uncluttered by what we call the facts of history, which are just after the events.

Howard’s stories are real because they take us back to a time when there was no egotistical reality, no opinion. There were just events and people’s irrational views of them. This means the reality that people experienced was meta; it was connected to unconscious dreams, desires. His tales are very true to that type of situation.

What this means is that a world of fact, or news, splits the mind from introspective reality, unconscious desires, images. But this is a lot of the content of history. You can attach facts to history, such as dates and dynasties, but the sense of mythopoeic reality that an Athenian or 16th century Dutchman experienced is lost, and that is visible in art.  Bruegel the elder, hunters in the snow

Bruegel the elder, hunters in the snow

What that means is that a world of facts replaces a world of unreality – of the mind. Facts will replace unreality and so you eventually inhabit a world where unreality is limited to pulps. The Junto, it seems to me, reflected an old world that was composed of style and content – a simpler one – the desires and urges of intrepid adventurers. The content of that world is much more introspective desires and their interaction with events. Thus is a style born.

The world as described exists in a balance between the unconscious and the visible. You can call it magic realism but you can’t call it fake. What you see when you read a newspaper is a description of a world that has no interior reality. The Junto –along with Howard’s other influences like Talbot Mundy – are being anti-political in describing an interior world, a dream world. But that world – which you could call unreal – is the one of Apollo and Dionysus, of dreams and urges.

Now, this makes a link between the 30s and the 60s very simple, since that is a description of “White Rabbit” psychedelia! There’s an obvious connection between the 60s and India, the Beatles and Ravi Shankar. Less well known is the link between Chinese culture, the mythic land of intrepid bandits and warrior priests, and Jefferson Airplane.

I think it’s essentially a dream image of China as the antidote to Western rationalism..

SKETCHES OF CHINA

..is not the China we know, it’s a dream fantasy of a land that once might have been. Hippy idealism is drawn to human cultures that are meta, that have a simplified iconography of naturalistic forms, that are not human-centric and rational.

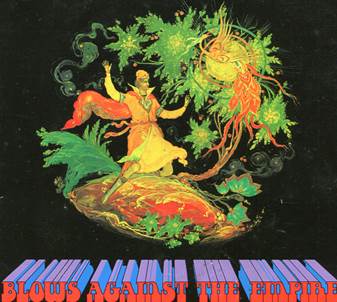

In ’67, the San Francisco art-scene evolved a poster style that reflected these interests. What you could say is the scene has an unreality about it a scene of the interior life that connects Man to unconscious imagery of naturalistic forms. The similarity between styles is seen in the cover art to “Blows” (1971), which looks like a hippy poster but is 19thcentury Russian folk-art.

Paul Kantner, Jefferson Starship

There’s also a similarity with art-deco forms, represented in comic art by BWS, who is also something of a medievalist. His prints and some of his comics are pre-Raphaelite influenced, as is well known. I guess you see where this is heading? The heraldic simplicity of that type of art has an unreality to it. In medieval times, though, the unreality was iconographic to the society.

In other words, unreality was actually reality to the society, meaningful images. It reflected the introspective nature of a certain type – the artist. The types of societies were much more similar to the ones portrayed by Juntoists than to more rational ones.

If all that is so, you have to wonder how “real” rational deterministic societies are that are guided by facts that owe nothing to human desires? Which brings us to..

Home