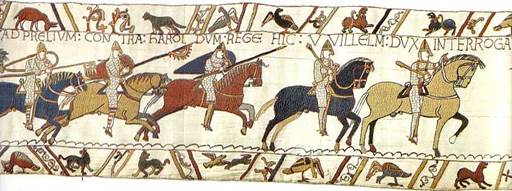

Tapestries are jaggedly woven continuous colored threads that quite often depict action, as in the Bayeux Tapestry (Tales of Faith 2)

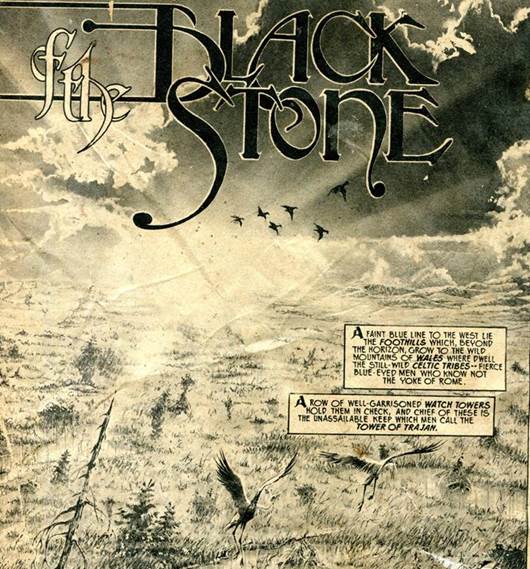

The events are “embroidered” with fateful omens, the ravens are circling. I’ve heard it said that Howard’s historical tales aren’t “under the dominion of fact”. The Bayeux tapestry tells with economy of grace of a battle, so the facts are all to do with action. Action isn’t factual, though, it’s the sequences of grace in motion, poised muscle in tension that are dynamically balanced, to do with conquest, life and death.

Once the action is finished – won or lost – then the facts are ascertained. Then they can be embroidered, and the skill was quite a feminine, decorative pursuit, flow of line and color of-a-piece. So the embroidery is telling of an action that becomes fact; it’s not telling of a fact in the abstract sense. It seems to be the case that, in the man’s world in which we live, abstract facts are the main reality, and not action.

Yet, the more you have abstract facts, the less seems to be there. In nature there is jaggedly continuous action, sounds, songs, whispering in the night, crickets in flight. The continuity of the action is expressed in time, so it is not rule-based. You could take Talbot Mundy’s hugely influential The Eye of Zeitoon as a case-in-point. There are rumours of the impending massacre but, against that backdrop, the four adventurers take to the hills and are intermittently engaged in fight-or-flight encounters.

It’s very telling that in most encounters, the characters are really nervously balanced and indecisive, and everything depends on their reflex responses at the time. The gypsywoman Maga is emblematic of this, dancing on her stallion, grabbing a mother-o’-pearl plated pistol, spying Will and gallopoing to claim him with lusty indiscretion.

The scene at the wildswept kahveh is poised on a knife-edge as the Turks are told to throw down their weapons, and only resolved when Maga disarms the lieutenant “with panther suddenness”. There’s no such thing as abstract competition in nature, only action (or standing still and silent in readiness, steel-sprung.) That is what happens throughout the story where people take sides and are largely indecisive.

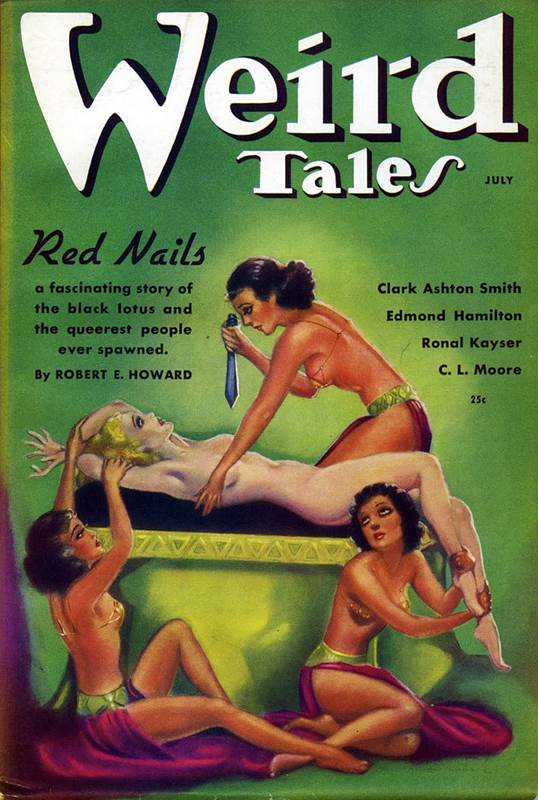

Our societies aren’t like that for the obvious reason this is a story set against a romantic backdrop, a polyglot wandering community of different types. Against that background there is no abstract competition, all is dynamic tension taking place in time. Now, this is the sort of ancient romantic society where tapestries – wall-hangings – abound, and that lend themselves to frieze-like depictions of action. Margaret Brundage’s covers to Weird Tales have that sort of frieze-like tableaux.

We who live in rule-based societies find it hard to visualise societies as the continuous, weaving linework of a tapestry where every line depicts acts, or comments on the action symbolically. Yet that is reality as seen in time, to a bird or a bee flitting through the air. Is it that we are not as alive? We are told that abstract facts are reality; they’re rules, that’s all.

A world of action is very natural and not factual – facts come later. “Facts” that give us a rule-based society and therefore not one based on action that takes place in time with a sense of proportion. A tapestry is a natural depiction of a society; our world has facts as things in themselves, which is an unnatural state of affairs, disproportionate and gross. If something cannot be rule-bound, then it has to be expressive; intelligent in its own physique, psyche.

Those are the two aspects of society and, actually, both are seen in The Eye of Zeitoon. The German Quedlinburg and his Turkish officers are much more rule-bound than our four adventurers or the intrepid Kagig. Since this is a romantic adventure, they come out on top. The ramshackle habitats and the hilly terrain they wander through are far from organized; you can almost imagine the rugged hill-towns and kahveh emerging fully-formed in the wilderness (this is a type of “being”, of merging with natural forms that you see in Roman bridges and aqueducts – see Hyborian Bridge 2).

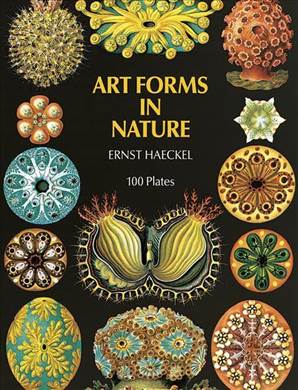

That type of architecture has a sense of spontaneity ingrained in natural forms, what you could say is the opposite of neat planning, like Lil Abner’s Dogpatch is a self-organized mess. The idea that nature is self-organizing, that life formed spontaneously from sea and minerals, is quite an old one. Ernest Haeckel has a whole book on it (Alan Moore cites Rupert Sheldrake in The Mindscape of Alan Moore)

There is an inevitability to the symmetries of natural forms. This is the side of nature that exists in time. As I’ve been trying to point out, modern acolytes of Darwin make of it an ideology, a logical order (struggle and the monetary system). But that order is actually the opposite of nature if the symmetries of nature are completely spontaneous. What you see in a William Morris wallpaper; a freeform, subtle and rambling, motifs of flora and foliage (the Rennie MacKintosh Glasgow School of Art that burnt down).

William Morris (Leicester)

The idea that nature is spontaneous is totally opposite to saying it’s rule-based. However, it seems fairly likely that Adam Smith’s natural state of liberty, and Rousseau’s natural social justice do assume that. You could add Ralph Waldo Emerson’s homespun Christian morality, and Walt Whitman’s pantheism. Anything rule-based becomes associated with living as a type of regimented cradle-to-grave affair, and not with the irrational, a lifecycle that gives meaning to the great unknown.

Oh, bard of Avon, thou whose measured muse

Most sweetly sings Elizabethan views

To shame ungentle smiths of journalese

With thy sublimest verse, what words are these

That shine amid the lines like jewels set

But ere thine hour no bard had chosen yet?

Didst thou in masterly disdain of too much law

Not only limn the truths no others saw

But also, lord not slave of written word,

Lend ear to what no other poet heard

And, liberal minded on the Mermaid bench

With bow for blade and chaff for serving wench

Await from overseas slang-slinging Jack

Who brought the new vocabulary back?

That rings true with the type of expressive slang Fred employs and they indulge in persuasively.

But it did better than put us in rising spirits. It convinced the Armenians! That foolish jargon, picked up from comic papers and the penny dreadfuls, convince more firmly than any written proof the products of the mission schools, whose one ambition was to be American themselves, and whose one pathetic peak of humor was the occasional glimpse of United States slang dropped for their edification by missionary teachers!

"By jimminy!" remarked an Armenian near me.

"Gosh-all-hemlocks!" said another.

Anglo-American patriotism in the days when it durn well meant something! Life and lifecycle in a non-material world, fate and destiny. The soulful songs that rise to the lofty mistral; shambolic places where hearthfires play moving shadows on iron-willed features and dusky damsels. Like Howard, the story is not so much factual as truthful in spirit. That is where you can say a society that exists in time is far superior to one which is rule-based, regimented and atomic (Grace Slick’s “Hyperdrive”, CH5). The society that America has become is life as routine, almost a denial of death (“pro-life” campaigners are plumb barmy, aren’t they? Let the woman decide.)

In Weird Tales and in Mundy’s grand yarn there is this great sense of life weaving against death, and the fates conspiring to aid or deny (much like Greek legend.)

Out of departed yesterday is grown to-day;

Out of to-day to-morrow surely breaks;

Out of corruption the inspired awakes;

Out of existence earth-clouds roll away

And leave all living, for there are no dead!

"Bismillah! Ye have heard a man talk! Now show yourselves men, and obey him, or by the beard of God's prophet there shall be war within Zeitoon fiercer than that without! Take counsel of your women-folk! Ye—" (he used no drawing-room word to intimate their sex)—"are too full of thoughts to think!"

What “they” tell us is real is the human head attached to various appliances, a psychosis of thought. Maria Callas, “Think – but not too much” (Pictorial 20). Romance may to us appear unreal because it deals with the things you can’t see; the twists of fate that give life meaning. That is life as lifecycle in the great unknown in Anatolia or Old America.

ME AND MY UNCLE

Fate coils round us like mist rising on the dawn of Beirut Dagh. We don’t see it because we are too busy thinking the thoughts “they” give us, a psychotic addiction from some Martian plateau.

Zeitoon itself is a mountain, next neighbor to the Beirut Dagh, not as high, nor as inaccessible; but high enough, and inaccessible enough to give further pause to its would-be conquerors. Not in anything resembling even rows, but in lawless disorder from the base to the shoulder of the mountain, the stone and wooden houses go piling skyward, overlooking one another's roofs, and each with an unobstructed view of endless distances. The picture was made infinitely lovely by wisps of blown mist, like hair-lines penciled in the violet air.

”thingness”

Tim Conrad, Worms of the Earth part 2 (SSOC 17)

City of London from Tower Bridge

no thingness

Indecisive, wavering, fearful, ever-alert and wary, brave and swift, lethal.. In a wildernesss, or the type of guerrilla action of The Eye of Zeitoon nothing is that certain. How is it, then, that our decision-makers are full of confidence and so assured, as they wreck things some more? The answer is it’s because they’re wrong that they feel so right!

Home