Netune

The great American milieu has proved inspirational to Europeans. In French comics (BD) for sure, but also in pop-culture generally; Gainsbourg's “Le Nouveau Western”, for example; Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend (incidentally, Jean Giraud's Lieutenant Blueberry was modelled on actor Jean-Paul Belmondo.)

The thing with America is it is very good on history. The markers are all along the highways (Neil Gaiman's American Gods is based on that, as I recall.) In fact, almost everything of note is history (R. Crumb is walking history). The amount of research material on Robert E Howard alone is astonishing.

It's just a trait, seriousness, and you could say it sometimes pays to be unserious, flippant. I read an article on Haight-Ashbury which admired its evocation of an era, while ragged youths were drifting round the Golden Gates area and tie-die stall-holder Sunshine Powers’ charity try to house them. At a symposium, there were some disagreements over the “Summer of Love”, and even if it ever ended (like Philip Dick says in Valis, “the Roman Empire never ended.”)

It seems what has ended is the capricious spirit of wilful abandon. The Jefferson Airplane song “Martha” about a runaway girl who just turns up at Kantner's town-house.. the sense of “the big society” (Grace Slick) as an organism where things just happen. The ideal encampment for people with no houses might be a tepee village; in other words, bring in some Indians, have them run round hollering and racing bareback to loosen-up the place. Not Haight-Ashbury I mean, since that is now “history”. It would have to be a little place in the country outside town. The ragged types could be bussed there and given the rudiments of hides and cords and pegs for tepee-making.

Indians know how to live wild and free, and Haight-Ashbury is now part of the great American study tour. Reservation Indians are part of the same tour, actually. Look, I’m not dissing it (a lot), just that there is a time to not be serious and concerned, a time to hang loose and free. Runaway white kids and tearaway Indian braves would be a culture-clash made in heaven. This is a revolution; there is no thought of organization or caring, just a wild get together. Don’t you already feel the attraction? Can’t you hear them drums a-beating?

In their day, the Airplane inspired migration to San Francisco. What inspires youngsters is a revolution – in sounds, in lifestyle, in costume and décor. The historical study and placing in aspic almost of a scene doesn’t reactivate it; it gives it another type of life, serious sincerity. Scenes in ’67 San Fran were looser, a cultural round of types who seem to gel, no aim other than the ability to be expressive. The hippy ideal of San Francisco, you could say, was to be non–factual, and it worked for awhile. Rough-and-ready scenes, squaws with no makeup, beat-up jalopies from the set of The Misfits.

It seemed like a time of both creation and destruction; when cast-iron facts were swept away by a colourful tide, a mythical time. Another way to put it is that the “man of fact” does not see myth. The two worlds are completely separate and he’s not in the scene, man.

This happens to be the theme of one of my favourite films, Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mepris (1965) with Bardot in her prime.

At the beginning of the film, Bardot reels off a list of her attributes (“mouth, arms, breasts..”) which Paul agrees he likes. “Donc, tu m’aime totallement?” Later on they encounter Fritz Lang at an Italian cinema and at Capri, where he’s filming “The Odyssey”. He comments to Paul that Odysseus is “un homme audacieux, simple et fidel.”

Paul has already made a fatal blunder with Bardot’s affections, and the theme of the film is the remorseless ways of fate, represented by the enigmatic sculpture of sea-god Neptune. The myths, in Godard’s film, are stronger than the modern “neurotic” man. He has lost the affection of Bardot/Penelope and can only plod on sadly to his destiny. The power of the myth is in the simple stylized sculptures seeming to represent timeless truths.

“The man of fact”, meanwhile, cannot see these truths which are to do with urge and desire, the “unthinking” acts which have an inbuilt style. The heroic simplicity of the stylized sculptures are inspired by the truth of urge and desire. Style is very useful for revealing inner content, as long as it’s not deviated by facts, so this applies to the irrational world of gods - or the medieval Christian world.

Medieval scenes, if you think about it, are cultural ecosystems; the quaint, the rusticky, the beasts of the fields, a world revealed by action and not by conscious plan. Style as applied to content, not the carefully formulated style of the modern world.

The pre-modern world is unthinking, in that respect, and so has a type of savage style about it. Godard’s film ends with a long pan from the actor playing Ulysses gazing out to Ithaca over the azure blue of the timeless Mediterranean. FIN. Savage lusts, inner urges and ardent desires animate the sculptures of yore. This is why they’re classical. There is therefore a clear connection between Indian tribes and ancient Greece. The psychological content is expressed in very strong style. These societies have the logic of desire so, to “our” way of thinking, they’re disorganized.

What I want to get in Indian lore is the playful, storytelling, visionary element - children are told tales of the Coyote, the Trickster, the semi-obscene Wesakechack. The dreamworld has a psychological strength that feeds the imagination. A society that has a strong element of kiddishness has a strong psychology, and that is a basis for order.

Our societies have a weak psychology; ancient Greek societies have strong psychology. The strong style of sculptures, of masks, is ever present, as with the Salzburg staging of Mozart’s Idomeneo (from 2006), the enigmatic seagod Neptune.

Idomeneo, king of Sidon, enters into a pact with Neptune, and is urged by the chorus of citizens to sacrifice his own son Idamente to appease the wrath of a sea-monster. They’re not political, they’re introspective and afraid of the god’s wrath. Two things are constantly brought together; introspection and a savage style in the story of the love between Trojan captive Ilia and Idamente. A stylized grace with a big green expanse of jagged stage, a single shoreline rock serving for a reclining Ilia. It’s a moment of repose in the tidal ecosystem of Neptune’s domain.

ILIA (SALZBURG)

Eco-culture is the tenor of the new society that is urged by strong desires to form settlements with strong psychological content. Song, dance, stories, campfire circles. Where you have a strong content, there is a vision to the society, a type of Apollonian order going back to 17th century Puritan communities living alongside mountain forest and tribe and livestock and stockade and dark sky. The inner life, the inner urge and the outer iamge reflect one another in some weird way, and are revealed in strong style, vernacular buildings, forest bridleways, civilization and savagery (see “Indian Summer”).

Two things are constantly brought together; introspection and a savage style. You get the same thing happening in Le Mepris, in the scenes set at Capri which are some of my favourite in film. As Procosch points out to Bardot, “look, how beautiful, the sea, the rocks.” The colours are captivating as Lang and Paul argue the motives of Ulysses, and Paul brings the same forelorn argumentative style to Bardot’s rejection of him.

The exact relation between style and content is difficult to judge, but it exists in a type of cultural ecosystem, as the citizens of Sidon do with Neptune in Idomeneo. As with any ecostyem there are cycles of death and destruction, regeneration and harvest, and the gods reflect this truth. Savage style and introspective reflection (content); the two things that seem to recur in something resembling natural harmony. The world of action that has an inbuilt style.

The melancholy romance of illustrated fairy tales are a good representative of this type of world. These classic art-nouveau illustrations have the mind swimming in a sea of possibilities. The mind – and for sure the young mind – doesn’t need facts to think. These pictures have a sort of abstract ambiance that feeds the content of the mind.

Edmund Dulac

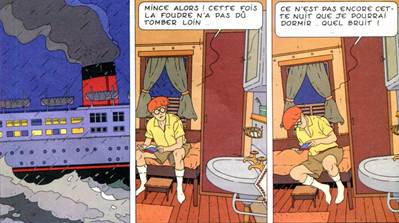

The fantastic power of ambiance is very hard to overestimate, particularly on children. It doesn’t have to be great works of art. As a kid I used to travel on ferries in the late 60s and the Tintinesque sense of rough-and-ready seafaring romance is still there. In heavy swells it was something else. Not much of that is really factual, but it is to so with the sea in an abstract sense.

The sense of abstraction is really the absence of facts, and the mind grabs hold of pictures, drama, action.. something like cinema. Jean-Luc Godard (who happens to be my favourite director) says that films are images, action not words; in fact this occurs in Le Mepris where Paul remarks he “wants to get back to the cinema of Chaplin, Griffiths.”

Action is rhythm, flow, abstract qualities like the surge of tides on the seashore. Where is all this leading? Just that in a world of facts the precise relationship between style and content is very difficult to hold on to. If there are no rough-and-ready ferries then there is less ambiance, less scope for introspection.

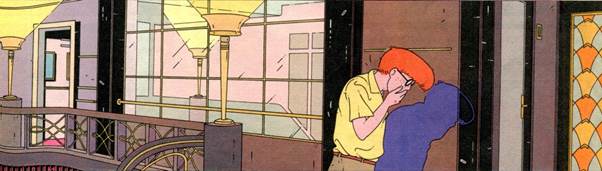

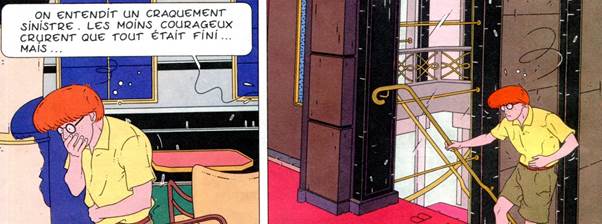

Les Aventures de Thierry Laudacieux, Riviere-Goffin, A Suivre 69, 1983

In a romanticized travel situation, the intricacy of detail on the voyage is one of the main delights. The ferry – or in this case the packet steamer of 1940s Mediterranean – is a floating island of colours and shapes with an organic sense of life. No offence to modern designers, but lived-in and musty is better any day.

The purpose of travel is not to get to the destination; you’ll get there once you’ve experienced the passage of time with a sense of rhyme. No jetlagging for old-school types. It’s travel in the Homeric sense of daybreak, nightfall, circular not factual travel. It’s basically the sense of romance because you get the same thing in pulp sci-fi voyaging through boundless space in beat-up jammers. Travel is a thing, voyaging on the seas of fate as Ulysses wanders his haphazard way back to Ithaca. It’s travel not as fact but as picture.

Another of the French New Wave films, Route to Corinth by Claude Chabrol, has Jean Seberg hitching a lift in a beat-up pick-up from a Greek Adonis. It’s grimy and noisy, also fishy as the Greek feeds her with sardines and, as day turns to mist-rolling night, they are in the middle of nowhere. Nevertheless, she has a swinging time on a Greek monument (in-joke for those who’ve seen it.)

Well, you can’t go wrong with Greek ruins, or undersea palaces.

Ryugu-jo, Undersea palace of seagod, 17th century

This basically points to two alternate futures; one has a strong psychology and irrational folklore that bears some relation to old illustrated children’s books and comics; the society is introspective and stylized with formidable ambiance. The other in theory has no ambiance and so no introspection atall! It would have no sense of lifecycle and regeneration.

Home