Metamorphosis 2

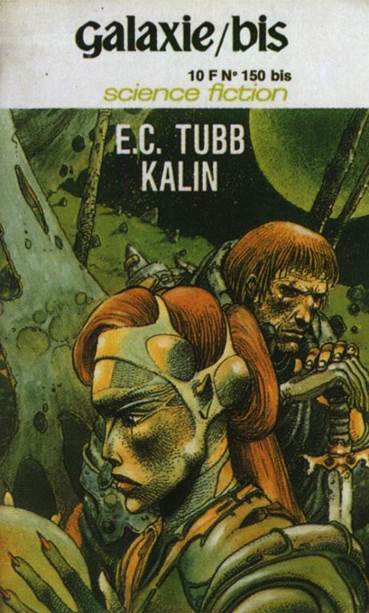

Dumarest #4, Bilal cover

This is where we came in (CH 1). I’m a bit of a fan of this planet-spanning pulp love story, and had the idea the tale of the “affinity twin” might be likened to a type of metamorphosis.

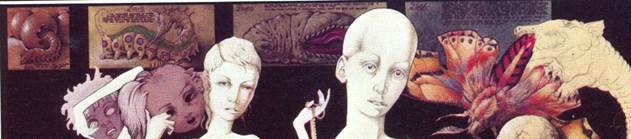

More specifically, a chrysalis or an erotic transformation, as with Patrick Woodroffe’s Polka. Woodroffe says

In the language of the entomologist, “larva” means “mask” and “pupa” means “doll”. Will the emergent moth, its wings scarcely unfolded from the chrysalis, be at once consumed by the predator? (Mythopoeikon, Dragon’s World, 1976)

Tereus Goes Birdnesting (detail)

Polka seems to have an aspect of metamorphosis, like a moth’s wings unfolding as wish-fulfilment fantasy, along with his personal cornucopia of snails, birds with human heads, dolls, tin men and so on.

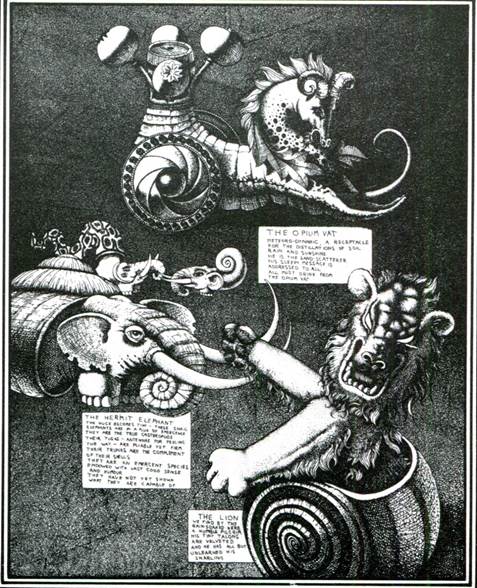

a heroic bestiary

In Kalin, she is in seductive guise as a flame-red-haired heiress, the affinity twin of an ancient, diseased crone, bloated and machine-fed. You could liken that to a lifecycle that includes degradation and regeneration.

“Nice, isn’t it?” The lips didn’t move as the voice drifted weakly past them..”Seven years, Earl. Five of them utter hell.”

The metal of the rail bent beneath his hands. “Kalin!”

“Yes, Earl, the woman you swore you loved. Not the eyes and skin and mane of hair but the real woman. The mind and soul and personality. The things which loved you, Earl, those things are here. The rest is a pretty shell. Which do you love, Earl? The brain or the body? Me or the beautiful shell? Which, Earl? Which?

He took a deep breath, remembering. This woman had saved his life, given back his eyes, given him her love. He released the rail and stepped towards the head of the bed. “Kalin,” he said. “I shall always love you.” And kissed the slitted lips. (page 182)

The inert container, a thing of primal, existential feeling I find quite Howard-esque.

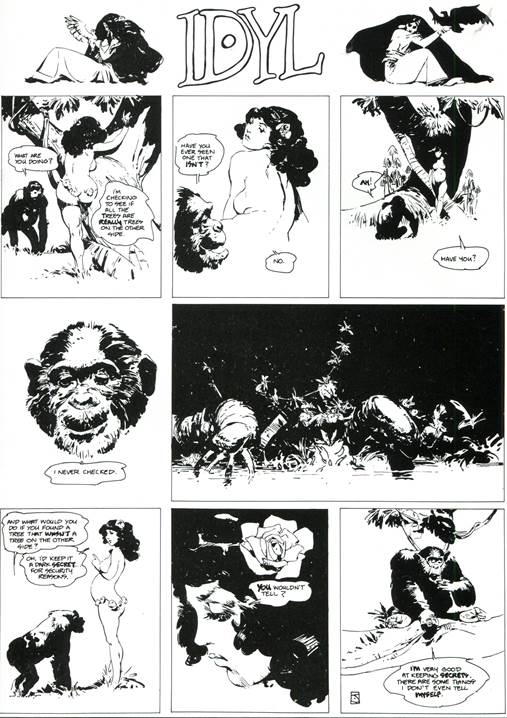

The weird thing about a chrysalis is that it is sort of inert, while the transformation occurs. With Woodroff’e picture of Crusoe, his degredations as a castaway have a transformation with a wish-fulfilling vision. Another conceivable instance of this is Jeffrey Jones’ Idyl since she is perpetually pregnant but never gives birth. Idyl is chrysalis as erotic symbolism.

1975

The transformative chrysalis, a lifecycle. Probably any transformation, such as the inert Greek masks used in tragedies, have that aspect. Or the weird beasts of heraldry that have become heroic pupae.

A lifecycle implies that nothing is as it seems, and there are catastrophic changes round the corner. Classical idealism has a lot of that in it, like something from a Claire Noto Red Sonja comic. Idealism is completely fantastical, in other words, incredibly dramatic and unreal, as well as symbolic and sexual.

Now, Howard Roark in the film of The Fountainhead, screenplay by Ayn Rand, has a speech during his trial in defence of idealism. In it, he says,

“The reasoning mind cannot be subordinated into an object of sacrifice.. of selfless joyless servitude.. He serves nothing and no-one.. Man cannot be forced into a race of soulless robots.”

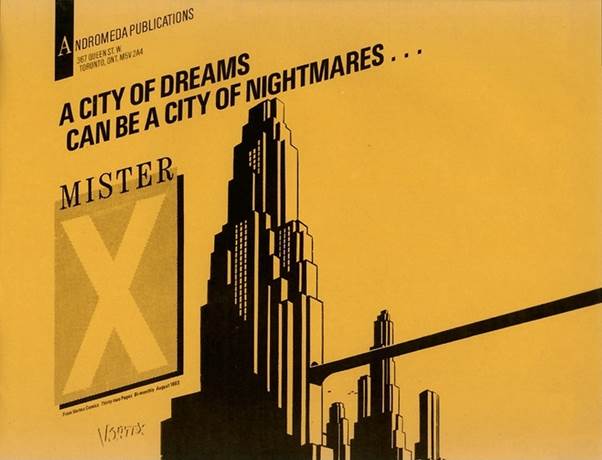

This soaring oratory is sold with soaring glamour, much like an ad for Randian futurism (see last 5-minute sequence with Patricia Neal). This is where it gets quite Mr X, from Dean Motter’s Radiant City.

Roark’s soaring idealism is itself robotic, as straight-line “my ideas are my property” idealism has no concept of abstract ambiance, or the visceral quality of cave-painting. The innovative real-estate mogul, simply by building, is trampling on unconscious imagery that feeds the mind.

Classical idealism is much more than ideas. It is the desires and unconscious urges of Man (not a man) rendered visible, as in the friezes and statuary of a Greek temple. There is a wealth of content in that – purely irrational, psychological.

This is exactly the type of interesting content that Rand doesn’t want, as “the world is perishing from an orgy of self-sacrifice” (like Rand’s dismissal of Kant’s Christian humility). The ancient world is a world of loyalty and honour and sacrifice and that is a lot of its content.

By idealising rationality, Rand is putting forward a false idealism that leads to robot servitude, downplaying all the unthinking, instinctive qualities that can go into classical art. Howard has a quote “concerning art” (Alternates 5):

I am by no means convinced that art is any higher than certain other forms of human activity, even according to the evolutionary standard. Such men as Michel Angelo, Poe, Beethoven, Cellini, Shaw are no more highly evolved than such men as Saladin, Napoleon, Genghis Khan, Robert E. Lee, Sam Houston, Thomas Jefferson, or James Corbett for that matter. The whole trouble with the viewpoint of purely mental workers is that they invariably underrate the mentality of other types of persons, and the intelligence required by other types of activities.'

Howard seems to downplay the Apollonian vision of great artists since – particularly in medieval and Renaissance times – they lived in “unthinking” milieux. A vision is not reality, it cannot replace reality, it is just appearance. A classical monument is vision given form, it does not replace the Dionysian urges and lusts that informed societies.

The glamorous finale of The Fountainhead is like an ad for the kind of revamped Randian futurism envisaged by the likes of Bezos and the Cupertino Mothership but, as I said before, that type of “glamorous” future has no subconscious symbolism of any description. What “they” call abstract architecture is just lack of content.

As CC Beck (Cosmic Curmudgeon) might have said, that's what “they” want, everything the same (though he said it of liberals). If you assume Bezos & Co are the logical inheritors of 1940s Randianism – which I doubt they'd deny – they are building the house that Rand designed, the high fashion palaces of futurism dedicated to pure profit. The simple fact is Randianism is nothing more than fashion, since it has no subconscious, no symbolism, no abstraction, no ambiance, no substance and is just empty style.

I'm not knocking it completely since there is something undeniably glamorous about Patricia Neal's lift-ascending finale; you get carried away by the star-hopping positivism! But, as with the Paul Rivoche Radiant City (above) from Mr X, dreams become nightmares.

The building that Roark designed for Wynand was financed by the sale of The Banner, and Wynand's little speech speaks to Rand's mindset. “The Banner is dead, it is financial fertilizer for your vision of genius.” This is a terribly rational way of looking at things and, while logical enough, contains no hint of the symbolism of regeneration and that things have a lifecycle. It seems implicit in Wynand's speech that he is thinking of death as an unfortunate finality (and in fact commits suicide!)

All that's very logical, but the ties between life and death are very strong and symbolic and almost certainly the oldest symbolism common to Man (as opposed to a man/woman of undoubted genius). If all that is off the cards you're left with the Wynand tower – a thing of high fashion and high finance – but no transformative lifecycle.

It's the symbolism of lifedeath that is transformative, and you don't get it in The Fountainhead because it is pure fashion, pure profit (Roark explicitly states that in his defence). For that type of symbolism you have to go to classical myth, to Daphne of the laurel, to Dionysus of the vine. The lifecycle has a melancholy aspect, but also an instinctive gaiety, a subconscious affinity with the shy, ferocious denizens of the wild (French ferouche, a description that has been applied to Melisande, the heroine of Debussy's Peleus et Melisande).

If Rand is a prototype of futuristic fashion, and if The Fountainhead is the template for Bezos & Co, it is an empty, joyless and frankly robotic future. It doesn't really matter how fashionable it may appear because there is an emptiness at its (Apple) core.

Home